|

|

The simple answer would just be "not at all."

I would understand why a very wealthy CEO who gained their wealth too easily might feel ashamed - - by inheritance or financial trickery, or by stealing or cheating, or by evading their fair share of income taxes. They might not want people to know how much money they earn, how much they pay in taxes, or how they earned their wealth. If so, then maybe those CEOs should be ashamed. |

But they're never ashamed for BEING wealthy. Just the opposite: many enjoy flaunting it to their peers in hope of eliciting some envy from their wealthy neighbors and associates. "Keeping up with the Joneses" is their constant struggle to keep up appearances and to maintain or improve their social status. It's all about narcissism and ego.

But why wouldn't an honest and fair CEO, who pays fair wages to their employees, obeys all the laws, and practices moral and ethical values? What would they have to hide? And why do they counter their critics with false charges of "class war" and "envy"? Especially when it is they who are usually the most guilty of this.

Time Magazine: Are Companies More Powerful Than Countries? U.S. corporations are moving beyond the national interest. And so are the jobs. "The top companies seem to exist in a world apart — they are booming, and their executives are prospering. If there is a meta-theme to this year’s World Economic Forum in Davos, it is that the world’s largest companies are moving on and moving ahead of governments and countries that they perceive to be inept and anemic. They are flying above them, operating in a space that is increasingly disconnected from local concerns, and the problems of their home markets. And if the conversations here are any indication, they may soon take over much of what government itself does."

Multi-national corporations are not about country first and never will be unless it benefits their bottom line. They don’t perceive the global marketplace and labor force in terms of borders or along political party lines. Their business models and strategies are based on a global economy and has been for many years. Multi-national corporations have adapted to a new paradigm, in fact they created the paradigm.

So maybe these CEOs should be ashamed.

The New York Times: The Good, Bad, and Ugly of Capitalism: "The eat-what-you-kill capitalism that Goldman Sachs represents is one that most Americans instinctively find repugnant. It confirms the suspicions many people have that Wall Street has become a place where sleazy practices are the norm, and where generating profits in ways that are detrimental to society is the ticket to a successful career and a multimillion-dollar bonus."

The banks went wild after the Republicans de-regulated them in 1999. But after the economic collapse of 2008, the Dodd-Frank bill didn't go near far enough to totally repeal the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act. Banks don't create jobs, but digital money, trading financial instruments back and forth. That is just plain shameful.

Rothschild Brothers of London, 1863. "Give me control of a nation's money and I care not who makes it's laws."

And that's another problem. Lawmakers make laws, but they don't enforce them. Corporate America understands that difference — and exploits it with a relentless regularity - and that's one reason why there is so much government regulation and complicated tax laws - the CEOs hire an army of attorneys and tax accountants to circumvent existing laws, while exercising a minimum of corporate governance in their quest for profits at any cost. The latest case in point: the battle over outrageous CEO pay.

You may recall in 2009, amid a flurry of negative publicity over excessive investment bank executive bonuses,

Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein asked employees to refrain from

a high profile, such as flashy or excessive purchases. Were they ashamed?

Towers Watson, the corporate consulting powerhouse, last week shot out to clients a cheat sheet for dealing with that “unflattering headline about your company’s executive pay.”

The Towers Watson advisory counseled CEOs to be prepared this coming

spring for news articles that may “mislead the reader into thinking” that your corporate board is taking “actions that are not in

shareholder's best interests” — articles with headlines like “CEO Pay Rises Dramatically in

2011.”

The Towers Watson warning could hardly be more timely. The new annual CEO

compensation reports will start appearing late next month, and all signs are pointing to another big corporate executive pay uptick, maybe as much as the 36.5 percent pay hike for

the top 500 CEOs reported for 2010.

Few analysts had expected this latest surge in executive pay. Two years ago, after all, lawmakers in Congress had written into law a series of curbs on corporate executive pay practices, as part of the widely celebrated

Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. (848

pages - PDF)

Dodd-Frank’s executive pay provisions give shareholders more information — and say — over executive pay decisions. And they give regulators much more authority to quash lavish incentives that encourage reckless executive behavior.

So what went wrong? Why hasn’t Dodd-Frank slowed the CEO pay spiral? Is

Dodd-Frank's approach to CEO pay reform somehow fatally flawed?

No one really knows — for a simple reason. Dodd-Frank's most far-reaching CEO pay provisions still haven’t gone into effect.

Who deserves the blame for this perverse state of affairs?

Courts deserve some. Last July, for instance, a U.S. Court of Appeals panel “vacated” a new rule federal regulators had prepared to put teeth into the

Dodd-Frank provision that could help dissident shareholders challenge corporate directors who rubberstamp excessive executive pay awards.

But much of the blame rests on federal regulatory agencies themselves. These agencies have been flinching, ever since

Dodd-Frank's passage, under intense corporate pressure. Regulators are dragging their feet and shying away from any real exercise of the new authority

Dodd-Frank gives them.

Last week, a U.S. Senate hearing flashed some light on that flinching.

The Dodd-Frank statute, Columbia Law School’s Robert Jackson told a Senate Budget subcommittee, entrusts in the

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and other federal agencies “unprecedented authority to ensure that bonus practices never again endanger financial stability.”

The SEC? Those who spend their time watching

porn rather that investigating

greed and corruption?

Under Dodd-Frank, Jackson explained, regulators can “prohibit any bonus that gives bankers excessive pay.” But an initial set of

Dodd-Frank regulations that federal agencies proposed last April, he noted, doesn’t even prohibit the most brazen of financial executive greed grabs, the “hedging” that financial executives do against their own company’s stock.

Executives hedge by placing bets in derivative markets that their firm’s share value will plummet — at the same time they’re stuffing their pockets with pay incentives to raise that value up ever higher. Hedging along these lines helped AIG insurance chief Hank Greenburg to $250 million when AIG collapsed in 2008.

On other Dodd-Frank executive pay provisions, it's not that the SEC and other federal agencies

have issued weak regulations, they’ve issued no regulations at all! The most glaring example:

Dodd-Frank’s now infamous — in corporate circles — section 953(b).

This obscure Dodd-Frank provision, guided into law by Senator Robert Menendez from New Jersey, requires corporations to annually reveal their CEO pay, the pay of their median employee, and the ratio between the two.

Menendez had a simple goal in mind. He wanted all shareholders — and all Americans — to know how much individual CEOs make as a multiple of what their typical workers take home. Corporate boards-of-directors do not currently have to reveal this

particular information

Corporate execs and lobbyists didn’t see this Menendez mandate coming. They were too busy working to water down various other elements of the pending

Dodd-Frank package to notice. Now they’re mobilizing feverishly to stop the pay ratio disclosure

Dodd-Frank mandates.

In the House of Representatives, these power suits have engineered Financial Services Committee

approval of a bill that would repeal the Menendez

mandate. But that repeal is going nowhere in the current Senate. Corporate America's

Plan B: Push the SEC to delay the release of the rules needed to enforce the pay ratio disclosure mandate...until the Senate changes.

Last month, 23 top national lobbying groups — a heavy-hitter line-up that included the

U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the CEO all-star Business Roundtable — sent SEC chair Mary Schapiro a letter

urging the SEC to “resist rushing into proposing regulations.”

The agency has so far resisted any urge to rush. President Obama signed Dodd-Frank into law in July 2010. The spring 2011 annual corporate meetings came and went without any pay ratio disclosure rules on the books. The spring 2012 annual meetings will come and go the same way.

And so might the spring 2013 corporate annual meeting season, since the SEC still hasn’t set any firm deadlines for getting the needed disclosure rules written.

This endless SEC foot-dragging has public interest watchdogs up in arms. Americans for Financial Reform, an umbrella group that includes the AFL-CIO, is calling the corporate

plea for more

discussions on the disclosure rule a cynical move “to stifle the rule, not to enhance the rule-making process.”

Lawmakers supporting pay ratio disclosure are pushing back, too. Representative Keith Ellison, a Democrat from Minnesota, last week began collecting lawmaker signatures for a letter pressing the

Securities and Exchange Commission to move forward with dispatch on the ratio rule-writing process.

- In 1980, notes Ellison, major U.S. CEOs averaged $624,996 in annual pay, about 42 times the pay of typical American factory workers.

- 30 years later, by 2010, big-time CEO pay had jumped to $10.8 million, or 319 times median worker compensation.

“Section 953(b) was intended,” says Ellison, “to shine a light on figures like this at each company.”

At last week's Senate Banking subcommittee hearing, senator Sherrod Brown from Ohio stressed that protecting U.S. taxpayers must mean

“putting an end to risky compensation packages that allow Wall Street to reap all the rewards when times are good, but stick taxpayers with the bill when things go bad.”

Not everyone on Capitol Hill agrees. The ranking Republican on the Senate Banking subcommittee that Sherrod Brown chairs, Senator Bob Corker from Tennessee, is feeling no angst about the nonexistent enforcement of

Dodd-Frank’s most important curbs on executive pay excess.

Corker last week declared that the Dodd-Frank regulations were “working.” We have “to be careful” on executive pay, Corker added, what with “populism running rampant” and people taking “about the 1 percent and the 99 percent.”

Why do we have to be careful? Any overly enthusiastic clampdown on executive pay, Corker would go on to explain, might have our nation’s finest CEOs pick up their marbles and go someplace else. Warned Corker: “Populism can drive a lot of talent out we want to see in the system.”

Oh really? That same talent, presumably, is what crashed the U.S. economy in

2008.

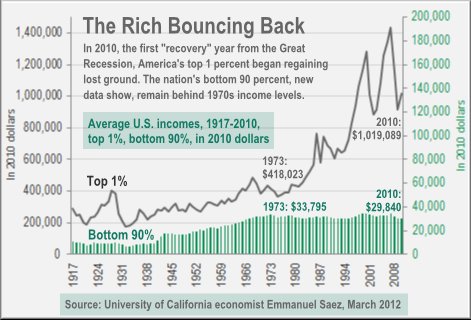

Regarding wages, income disparity, and wealth inequality, look at the chart below.

While CEO pay has skyrocketed, ordinary worker's wages are lower today than they were 40 years ago. And all while this was happening, tax rates for the CEO's corporations, their top income brackets, and their capital gains taxes are now historically low. Maybe those CEOs should be ashamed.

The average "effective" corporate tax rate is now only half as the much touted 35%, when they were over 50% in the 1950s. And the capital gains taxes on their stock options went down from 40% to 15% during that same period of time.

In a counter-argument about the tax treatment of stock options for CEOs representing a “windfall” for companies (because they’re allowed to deduct the full exercise value, rather than the often smaller grant value) Towers Watson admits that "many companies actually have a lower effective tax rate than individuals."

Over 30 years ago, in the generation before 1980, the world’s top industrial nations routinely subjected their highest income brackets to tax rates as high as 70 and 80 and even 90 percent.

But then conservatives swept to power in Britain and the United States — Margaret Thatcher in 1979, Ronald Reagan in 1980 — and obliterated steeply graduated progressive tax rates. By 1986, no dollar of income that America’s richest reported would face more than a 28 percent tax rate.

After the Bush tax cuts in 2001 and 2003, they bottomed out to their present day

lows...and all while American jobs were outsourced overseas for cheap labor and

domestic wages fell.

CEOs have increased their bottom line by hiring factory workers for $1 an hour and engineers for $8 an hour in places like China, then claim that Americans lack jobs skills. Maybe those CEOs should be ashamed.

While although we can't force CEOs to pay their employees a fair wage, at least we can tax them more fairly.

The Promise in the New White House Tax Plan

The Wall Street Journal columnist Daniel Henninger is calling the new budget the White House released last week “a work of literature.”

(What

Clint Eastwood would Do?) He means no compliment.

Henninger and his fellow apologists for grand private fortune consider the new Obama budget a work of reprehensible public policy fiction, a blueprint for “large wealth transfers” that amount to an unconscionable tax on “national success.”

Henninger and friends need to get a grip. Those wealthy paragons of “national success” they so admire would survive quite comfortably

with the adoption of any or all of the Obama budget's new taxes.

Indeed, even if Congress adopted every new tax this budget advances, not one wealthy American would next year face a top-bracket tax rate higher than 39.6 percent. Back in Ronald Reagan’s first term, income in America’s top bracket faced a 50 percent tax rate. The republic survived.

So why all the squeals of anguish out of right-wing fan clubs for rich people? Is the anger over the new Obama budget just more conservative political theater?

Not really. The tax proposals in the budget plan released last week actually do signal a turn — toward more genuine tax progressivity — on the part of the Obama White House. The

"Right" seems to sense that.

We can see this new White House turn in two proposals the budget for 2013 promotes, one narrow and quite specific, the other broad and vague.

The narrow pitch addresses dividend income.

Some background: The Obama White House has always supported the eventual expiration of the 2001 and 2003 Bush tax cuts for wealthy taxpayers. But the White House, until last week, has focused only on the Bush tax cut that sliced the tax rate on top income-bracket income from 39.6 to 35 percent.

Last week, for the first time, an Obama budget acknowledged that the Bush years had also cut the tax rate on dividend income down to 15 percent, from 39.6 percent. The Obama White House had previously let this tax cut slide.

Not anymore. The new Obama budget advocates an end to preferential tax treatment on the dividend income that goes to wealthy taxpayers. Couples making over $250,000 would under this new budget face a 39.6 percent tax rate on their dividends, the same as they did in the Clinton years.

Capital gains income, on the other hand, would continue to receive preferential treatment under the new Obama budget, only less of it. America's wealthiest now pay just a 15 percent tax on the capital gains they make trading stocks and other assets, the main reason why they pay so little of their incomes in taxes.

The Obama budget has this 15 percent capital gains tax rate rising only to 20 percent. But the new budget has a plan to offset this continuing preferential treatment for capital gains. Americans “making over $1 million,” the budget proposes, “should pay no less than 30 percent of their income in taxes.”

The new Obama budget gives this “Buffett rule” no other specifics. This lack of detail doesn’t particularly matter one way or another right now, since Congress as currently constituted is not going to adopt the Buffett rule in any shape or form this year — and everyone on Capitol Hill knows it.

In this charged political environment, the new Obama budget essentially serves as a campaign manifesto, a declaration of where the Obama administration wants to go in a second term.

The big tax question on this declaration: Does the administration want to go far enough — toward its stated goal of “a simpler, fairer, more progressive tax system than we have today”?

The answer gets tricky. The Obama budget tax framework, if adopted, would no doubt leave the tax system significantly more progressive. A 30 percent millionaire minimum tax would all by itself have a substantial impact. In 2008, the last year with data available, the nation’s top 400 taxpayers only paid 18.2 percent of their incomes in federal income tax.

Add to this 30 percent Buffett rule the dividend tax hike and other proposals the White House reiterates in the new budget — the return to a 39.6 percent top-bracket rate, the repeal of the “carried interest” loophole that enriches hedge fund kings, a limit on the benefits the wealthy can claim from tax deductions — and the nation would have a distinctly more equitable and progressive tax code.

The effective tax rate on Americans who make over $1 million currently averages around 25

percent. In 2013, under the Obama budget, millionaires would likely average a federal income tax bill that equals somewhere between 30 and 35 percent of their incomes.

Not chopped liver. But not adequate either. The current White House tax vision for 2013 and beyond simply leaves too much money on the table — money the rich have siphoned off from America's 99 percent, money that could be rebuilding the American middle class.

A little history can be useful here. In 1953, the heart of our middle class golden age, taxpayers who made at least $1 million — in today’s dollars — paid far more of their incomes in federal income tax than millionaires would pay in 2013 under the new White House budget. Our 1953 rich, after taking advantage of every loophole they could find, paid taxes at nearly a 55 percent effective rate.

But we don’t have to go back 60 years to find an American rich more heavily taxed than our rich would be under the new White House budget. Just 30 years ago, after the first round of Reagan tax cuts, millionaires ended up paying, after loopholes, nearly 39 percent of their 1983 incomes in federal tax.

The 2013 budget won’t get us back to 1983, much less 1953. But the budget does move us in the right tax direction. That counts.

And besides, any tax plan that really steams our guardians of “national success” does offer pleasures

aplenty.

And then of course, there's also the matter of tax evasion. Maybe those CEOs should be ashamed.

And what was also recently pointed out in a New York Times article (Capital Gains vs. Ordinary Income), "the best approach would be to abolish the distinction between capital gains and ordinary income altogether and desist from using the tax system for any kind of economic or social engineering."

But after all is said and done, I suspect only greedy people are ashamed to have their personal earnings made public, but not because they're ashamed of their actions, but only because they were exposed -- and because it might raise a public outcry for actions that could "right" the wrongs of inequity of wealth and income disparity in this country.

Who knows...maybe they'll have to pay more in taxes because they refused to pay fairer wages in the first place. And they wouldn't have had to be so ashamed of what they earned.

|

A Typical Summer Cottage for the Top 1%

Forget the Hamptons! For over a century, some of the world’s wealthiest and affluent families have called Bar Harbor, Maine (and surrounding villages) home during the warm summer months. Current notable summer residents include George Mitchell, Tim Robbins, David Rockefeller, Susan Sarandon, and Martha Stewart. Others have included Henry Ford, the Rockefellers, the Morgans (JP Morgan),

the Vanderbilts, the Astors and William Howard Taft. |

No comments:

Post a Comment